Ije (pronounced eejay) – is a conceptual/expressionist mixed practice artist – primarily painting, poetry and installation (also sculpture, printing, photography and film). Her work seeks to reshape embodied notions, responding to encounters with time, space and change through making and documenting; generating works activated through colour, gesture, texture, layering, fabrication, repetition and reflectivity. Ije’s work is currently showing in our first #ArtspaceWindows exhibition at Arcadia and The Row. Following a discussion about the Black Lives Matter movement at our last First Thursday Artist Meeting, Ije kindly shared an essay she wrote for her MA in Fine Art at Birmingham City University, and then agreed to us publishing it here alongside the exhibition in the #ArtspaceWindows. Though perhaps more academic in feel that our usual offerings in this blog space, we agreed with Ije that Adorno’s ideas have a particular resonance with times such as now, when we are trying to find ways of understanding the mistakes of the past, and of believing we can move forward. It also gives us an insight into Ije’s development as an artist and so deepens our understanding and appreciation of the energy in her wonderfully bold and colourful work.

Contemporary Philosophy & Aesthetics

Professor Johnny Golding (Birmingham City University)

Ije

MA Fine Art: Option Module 1 (2015)

Adorno famously remarked: ‘But since, in all the world whose law is universal individual profit, the individual has nothing but this self that has become indifferent, the performance of the old, familiar tendency is at the same time the most dreadful of things. There is no getting out of this, no more than out of the electrified barbed wire around the camps. Perennial suffering has as much right to expression as a tortured man has to scream (hence it would be wrong to say that after Auschwitz you could no longer write poems)’ 1

What does it mean politically and aesthetically to suggest that not only can one “write poems after Auschwitz” but that one must do so? Discuss in relation to continuity/discontinuity, that “indissoluble something” as well as the role of guilt and suffering.

Adorno, himself a Jew, and a leading member of The Frankfurt School2 wrote a collection of essays in 1966 called Negative Dialectics through which he challenged the dialectical way of reasoning and in particular Hegel’s approach, which though it explained evolution, could not account for revolution. And it was revolution that Adorno said was required to address the society that created and made manifest, Fascism and the hell that was ethnic cleansing, exemplified by Auschwitz.

Adorno sought to address fascism on a philosophical, aesthetic and political level to highlight and expose how the level of indifference and disinterest, the mass cultural acceptance of the “bad other” within society can create the conditions where extensive and sustained levels of cruelty, victimisation, torture and ultimately eradication can be not only tolerated but participated in. How individuals within these societies become so inured that they themselves come to feel nothing but indifference.

“In a Star wars T-shirt, Armed with an Airfix bomber, The young avenger; Crawls across

the carpet; To blast the wastepaper basket; Into Oblivion

Later, Curled on the sofa, He watches unflinching; An edited version; Of War of the Day,

Only half-listening; As the newsreader; Lists the latest statistics

Cushioned by distance; How can he comprehend; The real score?3

Adorno’s concern was that society must be able to understand how Nazism could have occurred in the first place, to learn from the experience, and start to open the way for new paradigms of thinking that may prevent recurrence. Capitalism, according to Adorno produced a culture whereby racism could not only flourish but was a requirement. Fascism totalizes by first establishing an us vs. them and for the Nazis this was Arian superiority where the Jews (as well as race, sexuality, religion) were the them, the bad who required removing from the system to protect the resources of the “fatherland” and the resultant genocide was the absolute integration, the eradication of the other.

As a theorist Adorno addressed the need to understand how this cycle of fascism, the us vs. them in cultural development could be sublated, how the grittiness of humanity’s surface could be kept open and how hope through art can provide a mechanism in its rehabilitation, the indissoluble something. This identified the fallacy of Hegel’s logic where as it didn’t deal with the issue of “something” the residue that remains. Whilst Hegel was clear that knowledge forms the basis of truth Adorno argued that it needs to be fully formed as a concept and open in such a way that it can change; that truth is always already mediated and that Hegel didn’t go far enough, whereby the sublation and synthesis only begins the process of change through unfolding but it is through negative dialectics, of seeing the ground as a mechanism for certainty and therefore allows for doubt which enables the individual to change.

What he did not do was to specify how this opening could be situated in reality and thus far from history post Adorno we continue to see the waxing and waning of powerful, controlling regimes, where the circle has been closed, where governmental approaches are often based on a lesser of two evils which does not prevent genocide and atrocity of varying scales as a result.

So, how and why could/would one write “poetry after Auschwitz”? Adorno uses “poetry” as a metonym for all modes of cultural production, for art, so to make poetry is todream, to imagine, to be curious about what the world could otherwise look like; the ability to communicate that which appears non-communicable. The problem of communicating large scale suffering and catastrophe inflicted by humans upon humans is that the artist is required to bear witness, to illustrate what has occurred, bringing it forth into the light of day from the shrouds of dark concealment. If the artist was not there how can they truly represent the magnitude of suffering and if they were there how can they bear to relive it without censorship or sanitization?

Helling states that this challenging paradox of communicating the non-communicable is a requirement “of all new and advanced art that is inclined toward becoming autonomous from society’s narrow conceptions of communication and expression”4 , where artists are pulled by this crisis between obligation and impulse of expression.

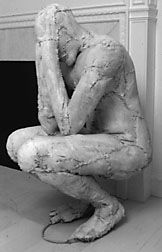

One such artist who struggles with this dichotomy is Balka Miroslaw who grew up in a Polish landscape of national suffering that bore the physical and emotional scars of World War II and the destruction and desecration of the Holocaust. As Young discusses: “He carries with him the burden of a history that was not his making, the memory of a past that is being made constantly for him”5

The Salt Seller, 1988; Wood, cement, fabric, salt; approx 120cm high. Balka frequently uses salt, soap and ash as well as wood, cement, paper and metal in his work as indicators of absence and loss, bodily residues, the traces of life and sorrow.

Adorno was not however talking about making art as pre-Holocaust, because to produce art in the same way was to participate in the perpetuation of that barbaric culture and at the same time run the risk of becoming a commodity, to be making a profit from totalitarianism and genocide. To survive reality at its most extreme and grim, artworks that do not want to sell themselves as consolation must equate themselves with that reality. Radical art today is synonymous with dark art; its primary colour is black.6

Progress is a requirement of a civilised society, not the blind steerage to preserve the status quo and Adorno asserts that both continuity and discontinuity is required, an amalgamation of progress and of regressive reflection, and a balance between the needs of the individual and the needs of the societal whole, in order for a good life to be lived, although Cook7 criticizes Adorno as he resists expanding on what a good life and a moral life would be like. However in his earlier work in Minima Moralia Adorno, whilst not directing how to live a good life, does identify that when making judgments, intelligence is a moral category that must be combined with emotion, that to imagine one can judge on intelligence alone divides the individual into different parts and in doing so makes them incapable of acting judiciously. That judgement is measured by the extent to which feeling and understanding can cohere. This balance then of what we take from history (continuity) and what we keep open and unpredictable or make new (the discontinuity), is according to Adorno where we need to learn from these big ‘events’ rather than allowing ourselves to become seduced by the comfort of the status quo, to be more capable of exercising autonomous thought, of finally discovering where an exit might present itself. Whilst individuals may strive to this, it is unclear to what degree societal development on a more global scale has been able to break out of the closed circle to unify continuity and discontinuity.

In 1988 the poet and activist Lemm Sissay was still writing about the insidious creep of issues like racism:

“There’s an Aids scare, there’s an Aids scare; but let you ear fall to the ground you’ll find racism everywhere (…)

Dormant racism can blow at any time; can be passed along the family line; sons and daughters

fathers mothers; friends and uncles and many many others

This dilemma doesn’t get coverage on breakfast TV; it doesn’t deserve the paranoia nor the reality;

but this epidemic is a killer you see; because the illness racism is hereditary”8

It is useful here to also understand that guilt is also involved either as a survivor or as a descendent of survivors/the society or land inhabited. Survivors of the Holocaust often questioned how it was possible that they had managed to evade death, after witnessing so many other lives senselessly extinguished, the torture, the dehumanisation, the callous indifference. Surviving atrocities of the scale of the Holocaust has commonly led to inward questioning of self, religion and “why?

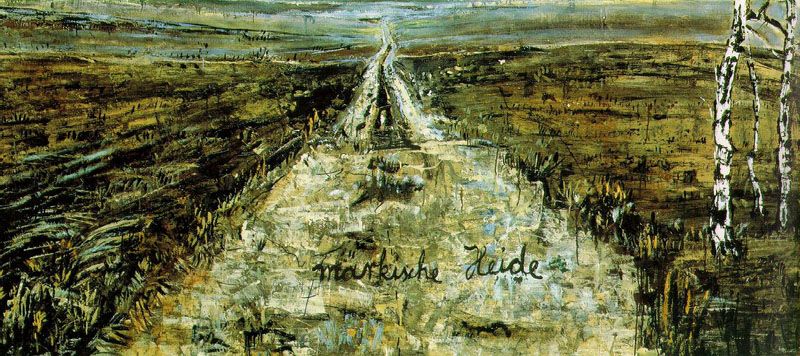

Anselm Kiefer is a German artist who spent “twenty years of loneliness” seeking a way to resolve Adorno’s “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric”, where his work such as Markische Heide (Brandenburg Heath) 1974 often featured the subjects of wastelands and barren landscapes interlocking recent German history with mythology and symbolism. His work exposing the suffering of the land, its commentary on societies suffering and atrocity, the despoliation as a result of war;

“ [T]hey suggest first his upbringing in rural parts of Germany ; secondly they refer to the idea that Germany was laid bare by the ravages of Nazism and awaits a fertilization of new life”9

Brandenburg Heath 1974; Oil, acrylic and shellac on burlap; h 118 x 254cm

Kiefer’s work has a physicality and sensuousness to it that is heightened through the use of the mythological and symbolic devices of the path, flowers, barren landscapes10 and trees, simultaneously expunge and expose suffering, sorrow and guilt. Through his work he seeks not just to address and atone his personal experience of guilt of being German but to excoriate the spirit guilt, of devastated societies, of humanity indifferent and as barren as the land has become and like much of Adorno’s theories he has a double meaning, through this excoriation, this exposure the “fields are manured by death” so hope and reconciliation are augured, the path leading one through physically and emotionally challenging terrain to

the horizon where our future may be. According to Biro:

“The horizon becomes the path through which the spectators self-consciousness is awakened (…) that to become self aware one, one must ultimately confront and consider the horizons encompassing one’s world”11

In considering this question I have also sought to look further, to gain greater insight into how Adorno’s theories and more specifically the role of suffering and this notion of the indissoluble something, that sensuousness of hope that levers an opening of progression for the future relates to my own art practice, for I have my own Auschwitz’s that I am driven to communicate to: “reveal the wounds of society”12

In so doing I made a piece to accompany this essay, which continues an ongoing body of work – Portents – considering our relationships, interactions and responsibilities with the earth; that through their portal qualities and depiction of landscape, seek to reconnect and speak to the viewer of that space between earth and the heavens – that alongside the pain, suffering and angst of the past/the now, there remains space for the sensuousness of life, for hope to be nurtured and for joy to bloom; to touch that place inside which reminds us of our interactions in the world and reignites our sense of purpose.

From Under The Sheet Black Clouds A Day Flowering (Brumous13 3); Acrylic, yarn and glitter on canvas; h120 X 120cm

“A rose in black at Spanish Harlem; it is the special one; it never sees the sun; (…) it’s growing in the street; right up through the concrete; (…) and watch her as she grows”14

It still appears to remain imperative to make art after Auschwitz if only to keep things open, to ensure that forward progress is maintained and because works of art are question marks.

“ But because for art, utopia – the yet-to exist – is draped in black, it remains in all its mediations recollections of the possible in opposition to the actual that suppresses it (…it is freedom, which under the spell of necessity did not – and may not ever – come to pass”15

Notes

1 Theodor W. Adorno (1966), Negative Dialectics, trans E. B. Ashton, (London: Routledge, 2004), 362

2 The Frankfurt School – the Institute for Social Research established in Frankfurt in 1923. The Institute was initiated in response to the belief that traditional Marxist theory could not adequately explain the development of capitalist societies in recent history and current times and they wanted to examine the possibility of an alternative path to societal development. They looked more broadly than Marx with an emphasis on critical theory.

3 War Games by Derek Stuart in John Foster, A Fourth Book of Poetry (3rd edn), (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1985)

4 Helling 2014, 133-134

5 James E. Young, Miroslaw Balka’s Graves In The Sky, in Miroslaw Balka, Topography, (Oxford, Modern Art Oxford, 2009) 178-182

6 Theodore W. Adorno “Aesthetic Theory” in James Helling, Adorno and Art: Aesthetic Theory Contra Critical Theory, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 1

7 Deborah Cook (ed.), Theodor Adorno: Key Concepts, (Acumen, 2008), https://ndpr.nd.edu/news/23859-theodor-adorno-key-concepts Accessed 2.1.15

The main reason why right living is blocked is that, in Adorno’s judgment, “late capitalism is evil to the root” and “this evil is particularly grave.” This is most clearly seen in “the moral catastrophe of Auschwitz” (p. 100). We live in a society where, no matter what we do, our actions implicate us in societal evil: either we inadvertently help maintain the societal system or we directly contribute to it. Swayed by ideologies that shore up the status quo, we become ever more enmeshed in the system, ever less capable of autonomy, of determining for ourselves what is the right thing to do. Because living rightly is virtually impossible, moral philosophy lacks a substantive basis from which to provide an ethical theory.

That is why Adorno regards all the moral philosophies on offer as inadequate. A formal Kantian ethics of conviction relies on intentions that either cannot be actualized or lead to disastrous consequences. A more substantive Hegelian ethics of responsibility presupposes a good social fabric and endorses the status quo. Nor would Nietzschean revaluation, existential authenticity, or Aristotelian virtue ethics fare any better.

8 Aids (Racism Came To The West Also) Lemm Sissay, Tender Fingers In A Clenched Fist, (Bogle L’Ouverture, 1988)

9 Thomas McEvilley, Anselm Kiefer: Let A Thousand Flowers Bloom (London: Anthony D’Offay Gallery, 2000) 12

10 McEvilley, 2000, 12 the Barren Landscape theme refers to the Waste Land of the Grail Romance (…) the once fertile earth was laid bare because its king had suffered a wound in the thigh, like Aphrodite’s lover Adonis gored in the thigh by a bull on a hunt (…) the thigh wound in mythological contexts is a surrogate or euphemism for genital wound, and renders the king – and his kingdom – infertile. The cause of the Grail King’s wound is never clear, but seems at times almost metaphysical, as if it were caused by some fundamental lack in things, some ontological hole gaping through embodied life, for which the Grail, which has been taken from the Waste Land as another cause of its bareness, is the only remedy. The restoration of the Grail and the refructifying of the Waste Land is the goal of the Grail Knights. McEvilley goes on to posit that the affliction in Kiefer’s Waste Lands seem to be World War II and later Chernobyl and other despoilers of sites

11 Matthew Biro, Anselm Kiefer (Phaidon Focus), (London: Phaidon Press Ltd, 2013) 44-45

12 Helling 2014, 134

13 Brumous – a term I use to describe spiritual and physical feelings where I and/or the landscape are abounding with fog or

mist that has a weight to it, a depth – it is both enveloping and cloistering; a winter coat for protection that becomes saturated and too heavy to keep going unless it is removed or the sun comes out to dry it off and lighten the load

14 Aretha Franklin, Spanish Harlem (1971), (original lyrics by Jerry Lieber and Phil Spector, 1960)

http://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/arethafranklin/spanishharlem.html Accessed 23.12.14

15 Helling 2014, 1

Bibliography