Warwickshire based artist Janet Tryner has shared with us her experience of attending our Exploring Collections Workshop and what she then went on to create in response to this…

“Back in February I was fortunate to have participated as an artist in a Working with Collections Workshop held by OutsideIn and Coventry Artspace and lead by artist and curator Tess Radcliffe.

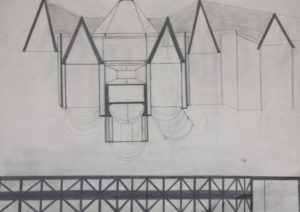

Image: Drawings from the OutsideIn Collection.

Part of my current practice is to form collections during research, mostly of found objects, litter, pebbles and similar, so I thought I’d find something interesting in looking at collections made by someone else. I suppose I am curious about the links between them; how gathering dissimilar objects together causes their meanings to reverberate and become reshaped, sometimes twisted into something entirely different. However, a collection of art is an entirely different gathering to my odds and ends.

It was made clear over the four days, that the OutsideIn art collection came together in various ways; some were pursued, some were donated, some carefully selected. There is overt strategy to collect in order to adjust societal accumulation of art, a cultural wealth that connotes status and directly relates to how a nation portrays itself, in order to increase representation from people who in the past were subject to exclusion by gatekeepers to art institutions, and therefore have not experienced opportunities to access an art education and career, often were, or are, incarcerated within hospital or prison systems, or who belong to one of the many other less privileged parts of society due to class, health and skin colour.

As with my collections, the reasons for gathering are not often apparent in individual parts within the collection when looked at in isolation. Objects of art are disparate and sometimes it is difficult to see how they work together. To me this is a fascinating task of curatorship: questions and discussions over how to convey the value in the meaning of a single work and enhance, or even to twist it, in connection with another, or others.

You can view the collection we studied here: https://outsidein.org.uk/exhibitions/collection/ but I’m not going to go into further detail about the collection as a whole, other than to say we spent several days talking about the examples of Outsider Art that comprise it. Some works came with a lengthy backstory, and some with nothing more than what you could see in the frame. These felt more like my collections of litter, some of which are so mangled that I cannot guess at their past use, so perhaps it isn’t a surprise that I was drawn to one of the more enigmatic examples in the group; a pencil drawing called ‘House with wings’ by Albert, a long-term psychiatric patient, whose architectural style drawings of houses are often not pinned to a representation of three-dimensional space and so veer off to the edge framing a void in a way that is both charming and worrying.

Albert ‘Building 3’

Albert’s work varies little stylistically. He uses repeated geometric shapes – squares and triangles, similar thicknesses of penciled lines. His houses are childish and stubbornly transparent; recognisable in the style of British interwar housing but also as a toddler’s set of wooden building blocks. They appear featherlight and have gone further than art-historically-informed surrealism into the land of the unreal; projections perhaps of many houses that he has seen but not been inside, for there is neither a sense he understands what you need to understand to design a house that will not fall down, nor is he interested in the idea of people living there. Nevertheless, he does have a grasp of how a floor-plan and a house should look like. I got a sense of him having observed many, many houses as he was driven past them.

My first response was to write:

Albert

In the middle of the night

I wake to make notes about rooves and the drawings.

He called one a ‘House With Wings,’

But this invisible house has a hovering roof

and lines that buzz in the wind; droning back and forth.

I want to know what happened to the rooms.

Is no one else in there?

None who went through the sitting room

shifting dust under sofas

and picking up mugs of half-drunk tea.

Where is the plan?

Did it escape through the faint windows?

What was in those slight boxes?

Because to render houses small

And so far away,

As other people’s houses are,

Is different to drawing the house you can stand up in.

I wanted to explore that sense of staring at houses out of a car window – something I enjoyed doing when I was a child, but of course now I am middle-aged I know something of the complex lives that houses are hosts to.

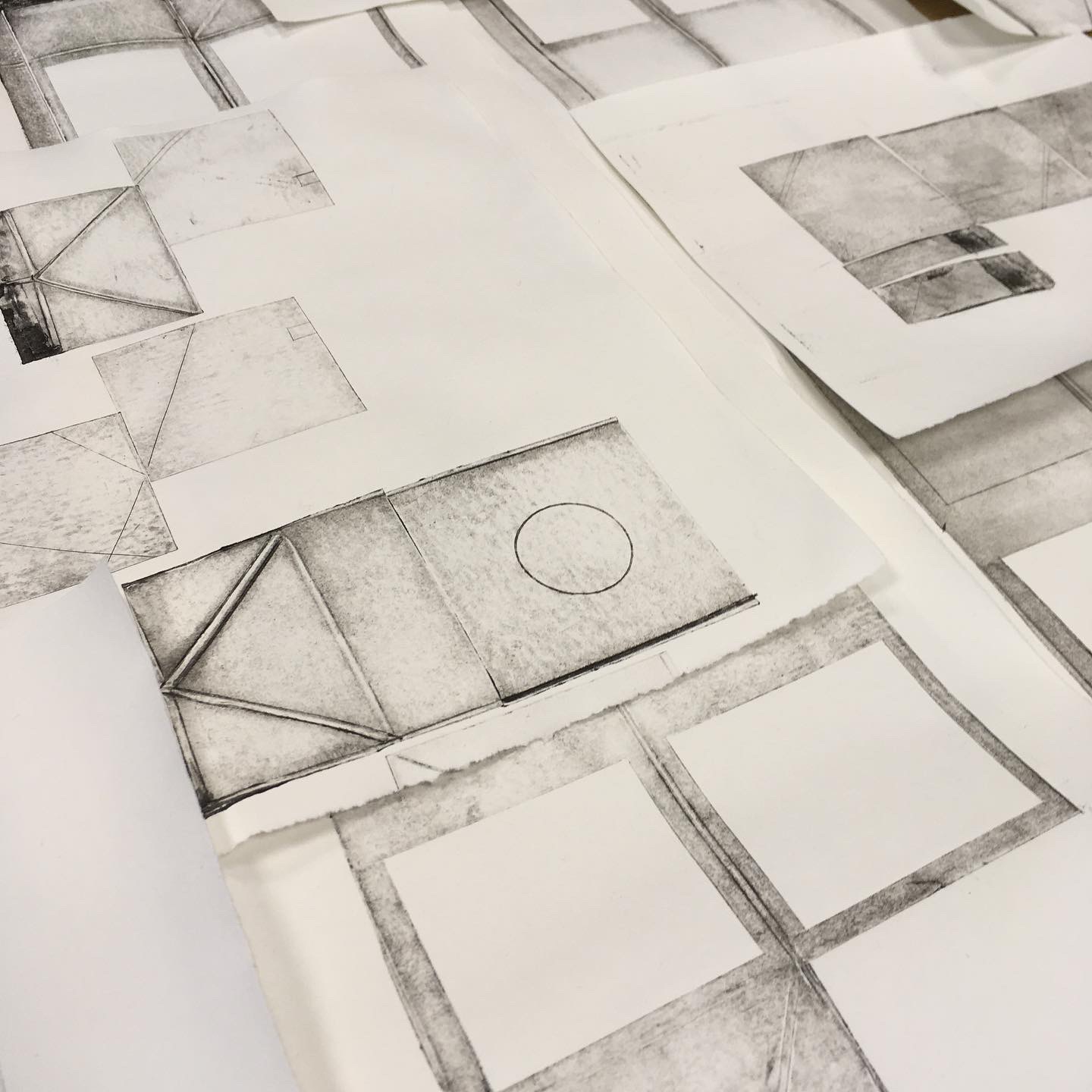

From the start I intended to use a cut up milk carton with my laptop screen to approximate the perception of passing by houses in a car, but where they would be more like Albert’s flat houses. Cut up milk cartons easily shift back and forth between 2d and 3d structures with their shiny creases betraying a connection between states. Their ability to flatten and stand up enabled me to experiment with that same offsetting of reality into make believe in Albert’s work, which enables him to play, the idea of using it as a printing plate came later.

Set up with milk cartons.

I thought that if I cut out enough triangles and squares out of milk cartons and put them through my printing press with dark ink them I might be able to achieve an imprint that would achieve a similar pattern of shapes, and the edges might produce similar varying widths of line, especially that really delicate, too light, pencil line. Yet this method would hold me back from exerting too much control over the end product, since I didn’t want to be copying his work, and this might help me produce a response that might reveal something new and surprising.

The printing plate ended up included in the video because of it aptly demonstrated the messy reality of the printing process.

This last image is the print I consider closest to my original intention.

***

Footnote:

I am aware that what I’ve written so far explains little of the title: Weird Value. This comes from a summing up of the workshop at the end by Tess, who said I’d shown her a value in objects, and I wondered what that value more exactly was.

Looking back over my last year’s work and amongst art, tests, experiments and ideas let go there are a number of new collections of litter, and I think I can detect a Weird Value in the things in my collections. Furthermore, I think this Weird Value is counted by emotions measured in negative objects. This is simpler than it sounds.

The things I’ve gathered are detached from their place, so as a collection their common thread is detachment. They are also doubly-detached, since they were lost and remain lost even after I found them and took possession of them. That’s their identity now. (I suppose they are also doubly owned – but that’s another thread.)

What is most important about this detached status is that I think it is ‘weird’ in the uncanny way of Mark Fisher’s meaning of the word: an unexpected thing in a place: an object in a place where it is not expected.

This reveals something about the place and our expectations of it and much less about the object – the object is strange and unknown; it affects our emotions only once we have processed our assumptions about the place it is now in. The thing is just the divining rod / messenger about the place.

The phraseology of lost things comes about over objects no longer anchored to a human. So they become uncanny because of the loss of the human. We don’t like to notice our absence from the world, generally.

So these lost things are now in the world without us. What I cannot not know is if they ever become of themselves, although still within the great conglomeration of The Earth. I think to us they always retain a relationship, so I think the only thing I can state truthfully is that according to us they have become things in the world, they are of themselves and they have human pasts.

This makes them ghostly. See where the uncanny comes in?

~

Moreover, the ‘Weird Value counted by emotions measured in negative objects’ is an issue over expectation of attachment. We expect for everything to have its place, but lost objects reveal how far we are swamped by the world of things. Things are immense in their multitude and far, far beyond us in their existence – their tenure on this planet will outstrip even the longest living of us living now and we can never hope to control their effects beyond our grasp, or imagine the rippled effects of our actions via their existence – those lost objects, all that waste, are our bodies multiplied.

However, it occurs to me that we actually expect certain of our modern urban places to be littered with our waste and misplaced objects as much as we expect ourselves and other human beings to use and lose things. Little bits. It’s part of our modern experience of the outside – the ‘out of doors’ it was called in the 18th century. Is there a sense that by polluting the out of doors with the things we are used to being with on the inside of doors we make that place more familiar? Setting down control. Making it ours. After all we can’t help but drop stuff. Every living thing does that. It’s part of being alive.

I think we want to remain in some contact with the ghostly things. We are drawn to them – they were our bodies. How spooky.

But this only partly confounds the Weird Value that I perceive exists – this running after ghosts. However, I think that although there is an expectation of seeing human traces everywhere, on another level we think that outdoor places are not ours to smother, and of course we hate the mess of putrid, ugly litter, it pollutes this idea of perfect Eden that prevailing religions teach us to reach for. This produces a supplementary Weird Value in out-of-placeness.

In my initial notes I also wrote, ‘So this weird value – measured in emotions inherent in objects – is to do with all objects, but I also think this emotional value is a negative figure.’

Did I imagine this negative figure to multiply from the moment an object is discovered, and go down, or backwards – perhaps as it becomes further lost, the further it gets from me? Yet, now, as I study an object, it reaches the nadir of its value – and through my study it turns and starts to come part of the way back. Do I make it positive (or less negative) as I turn it into an object of art and bring it back into culture? Obviously, it’s in association with, and observation by another human (me) that it turns. Duchamp knew all about this.

But does this actually happen, or did it reach the nadir of its value the second before I found it? The nadir would then be happening within the fullness of its ‘thing in the world, of itself, with a human past’. With my sensible head on I think not because the value must happen in connection with the valuing person. At the end of the day, I cannot be non-judgmental like a piece of metal foil balanced at the meeting point of ground and air even as we share the same space. What I am always dealing with, what I am always representing, is my human values, my human culture, and I can never shed these. However, I find appealing the idea of the thing in the world reveling in its deepest, grimmest negativity, as far away from us as is possible to go on Earth.”